Hong Kong-born writer Tim Tim Cheng shares the memories and languages that shape her award-winning work…

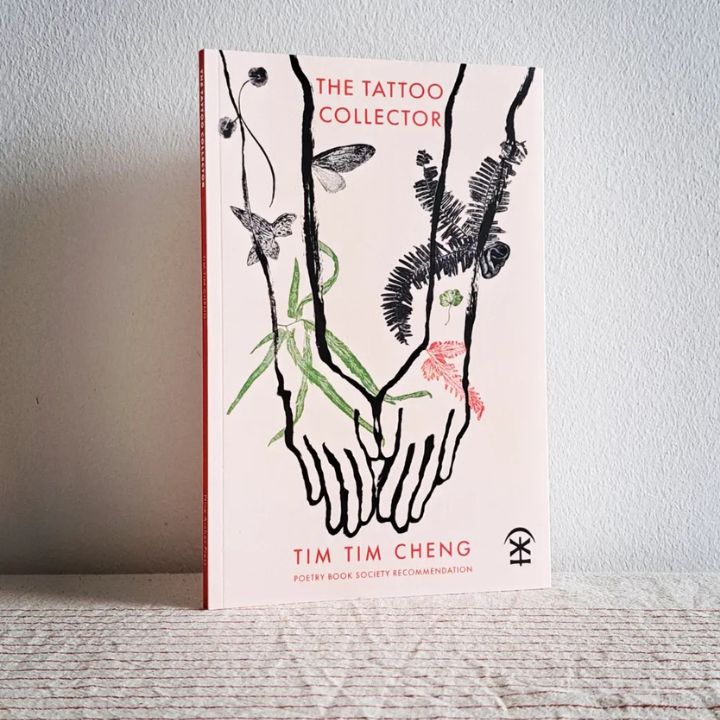

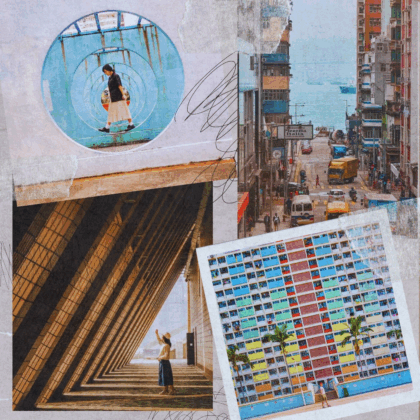

Award-nominated poet, translator and editor Tim Tim Cheng represents a new generation of Hong Kong literary voices, one that captures the city from — to use her words — the “fractures and fragments” of a hybrid identity.

Longlisted for the UK’s Jhalak Prize and shortlisted for the prestigious Forward Prize for her poem Girl Ghosts, Cheng draws from a deep well of personal history: a childhood in Tin Shui Wai’s public housing, raised by her Fujianese and Indonesian-Chinese grandmothers, and an existence caught between Cantonese and English. In doing so, she explores her relationship to the city not through the mournfulness typically associated with diaspora literature, but through that which she clings to — memories, encounters, languages learned, forgotten and returned to.

As she prepares to teach at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (in the English Department) and translates the works of local writers like Lee Ka-yee, Cheng builds a bridge between languages and generations, offering a unique portrait of identity, family and the things that disappear. We sat down with the multi-talented linguist to discuss ghosts, grannies and the stories that shape a home.

Can you tell me a little bit about your childhood in Tin Shui Wai, in the New Territories?

I lived with my grannies who hoarded. I remember being taken to the local McDonald’s for the air-conditioning and to the wet market for grocery shopping. I was told that the parks and the recreational spaces near the nullah, which we call the stinky river, were full of dangers and bad influences. I was always afraid of ghosts and vampires, so I remember being scared by loud engines (which sounded like vampires yawning) and the windows of the local kindergarten I went to.

A lot of films like to depict Tin Shui Wai as this sad satellite city full of migrants, as if the rest of Hong Kong isn’t full of migrants, too. I don’t want to deny this aspect; after all, social welfare could always be improved. But there is also a lot of joy. It’s a super walkable new town. I later taught in an art school, where I met a very sassy and talented student. Now an artist and model, they also lived in Tin Shui Wai.

Read More: Hong Kong Ghosts Stories — Haunted Spaces To Visit

Your great-grandmother and grandmother raised you, bringing Fujian and Indonesian-Chinese heritage into your home. How did their stories or traditions shape your view of identity growing up?

It was confusing. I was the first person in my family who was born and raised in Hong Kong. My grannies struggled to take care of me, my two cousins, my aunt and each other, who all lived under the same roof. Fujian tradition was more prominent in the family. I can still perfectly understand Hokkien, although I can’t speak it. The Indonesian side was brushed under the carpet, but I do remember my great-granny taking me to the local wet market to chat with her friends in an Indonesian language I couldn’t name or understand, and the times when my grannies made meat floss and chilli sauces together.

When I was a kid, I did not understand the tense dynamic between my granny and my great granny. Now I have learned to ask these questions: What is it like for my grandmother to be a mixed-race person, whose dark-skinned, Indonesian mother was a maid sold to China, whose father was a landlord who had to give up his land during the Cultural Revolution? What is it like to be a carer for a mother with dementia, four daughters, an unfaithful and gambling husband and three grandchildren for almost all your life? What is it like to bring your entire family to a new city because you think it is more prosperous and beneficial than your home city? I guess part of me is writing to figure all these out.

You’ve spoken about avoiding Chinese books when you were younger and described yourself as “BYELINGUAL,” caught between English and Chinese. Where do you think this feeling came from?

I wish I had asked myself that when I was younger! I think it came from education and a presumed sense of essentialism that I learned from growing up in a migrant family in Hong Kong. I went to an EMI secondary school in the early 2000s, where I learned most of my subjects in English. The overall atmosphere told us: “If you are good at English, you will succeed. Chinese will interfere with your English grammar. Chinese is less important as it is only one subject.” This attitude is reflected in the fact that there is a full scholarship for prospective English teachers, but not for Chinese teachers. I also grew up being a confused essentialist. I didn’t think I could be both good at Chinese and English. It’s always either-or.

Read More: 14 Uplifting Autobiographies & Memoirs By Remarkable Women

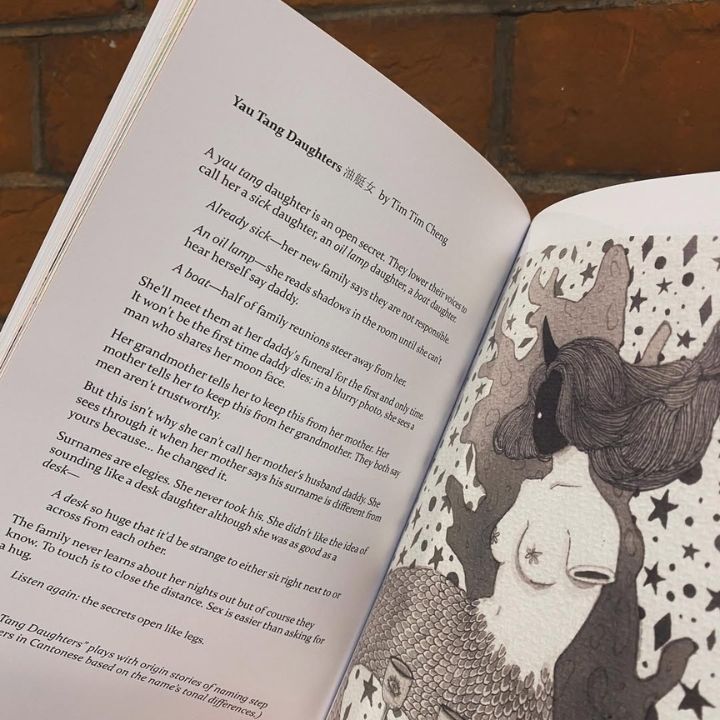

Your poem Girl Ghosts was shortlisted for the Forward Prizes for Poetry — congratulations! In it, we get glimpses of Hong Kong (fermented soy beans, winter melon, porcelain clattering in tea restaurants). How do Hong Kong’s sensory details show up in your writing?

I wrote the poem in the UK, but the ideas came from my conversations with my family during COVID in Hong Kong. I used to think writing about food and family was so uncool. So many Asian diasporic writers have done it before. But I took a Masters in writing, which made everyone submit 60 pages of poems per year, which made me miss home. I was confronted by the realisation that some stereotypes are true and do matter to me. So I tried to add my own twist to the genre, which is to make it less… sad?

The poem also deals with themes of race, gender and family. Do you find that poetry is uniquely suited to express complex aspects of your (or others’) identities?

100%. Poems are a great space for fragments and fractures! Sometimes essays require a thread that our lives can’t, or have yet to form. That said, recently I have been reflecting on how honest we could be in poems, and from which point onwards we don’t need poems, but prose, therapy, sports or a phone call to close ones.

Read More: Hong Kong Female Founders Share Their Life Lessons

You’ve split time between Glasgow and Hong Kong recently. What are some things you miss about Hong Kong when you’re away? Can you share some of your favourite spots?

I miss the ease of being a local person in Hong Kong. It actually takes a lot of energy to constantly audition yourself for new opportunities in a new place and operate in a second language. English used to be an escape for me when I was obsessed with bands from the UK as a teenager; now it’s work. I also miss the accessibility of harbour view and hikes and fishball noodles in Hong Kong. I love the public libraries. They are such free, comfortable spots for work and people watching.

You’re translating Lee Ka-yee’s essays now. How does translating other Hong Kong voices deepen your own connection to the city, especially from afar?

I am so grateful for Ka-yee’s trust. I saw her read her poetry to music a few years ago without knowing it was her. I have been using translation as a way to connect with the Chinese language, to force myself to navigate its differences from the English. But throughout the process, I understand that Hong Kong sinophone writers are also influenced by a lot of translated literature (in Ka Yee’s case, Michio Hoshino, Marguerite Duras, Olga Nowoja Tokarczuk and Rainer Maria Rilke). Hong Kong and other cities are always so porous. I also pride myself on being one of the biggest fans of Post Script Cultural Collaboration, a Hong Kong-based independent publisher. I have loved so many of their beautiful publications. Ka Yee’s book confirmed my love for the press even more.

Read More: What It’s Like Being A Woman In A Male-Dominated Field

Music is a big part of your story. Does your connection to music differ from that you have with translation or writing?

My connection with music is always a regrettable one. I love to sing. I used to learn the bass guitar. I think I lack a certain alignment for me to fully become a musician. But it’s on my bucket list. Translation and writing are part of how I am conditioned: sit in front of a laptop. My mother still thinks I am doing homework when I do freelance work!

Your poems include Cantonese and local references, including political ones. Do you imagine a particular audience when writing?

My first audience is always my future self, and then I hope this self relates to others. The audience is often full of surprises. I thought a person from Hong Kong would understand my references, but they didn’t. I thought a person from Scotland would not understand, but they did. An Egyptian teacher told me that they taught my frog poem to a primary school because the frog is a mythical figure in Egyptian lore.

Poetry has a bit more leeway, as there is less hurry in identifying an audience than a voice. As much as I am trained in Hong Kong and the UK, somewhere, someone else will find connections with you, and you will learn more about the world in that process.

Read More: Hong Kong Artist Lio Sze Mei On Escaping The Real World With Her Art

As you prepare to teach at CUHK, what do you hope to share with Hong Kong’s next generation of writers?

I am excited! I am not sure how many of my students want to be writers. But I think everyone can learn from great writings at the right time. It’s about opening yourself up to what the voice has to say. It’s about listening. I hope I could play a small part in that.

If you could tell your younger self one thing about embracing hybrid identities, what would it be?

I think I would tell my younger self that “it’s not your fault you feel uncomfortable in your own skin. When your inner critic judges, ask yourself if that is really your voice or internalised societal forces.”

Read More: What I Wish I Knew Before Turning 30

Main image courtesy of Tim Tim Cheng. Image 1 courtesy of Encounters Hong Kong, image 2 courtesy of Tim Tim Cheng, photographed by Chris Scott, image 3 courtesy of Charlotte Mui, image 4 courtesy of Tim Tim Cheng, photographed by Lesa Ng.

Eat & Drink

Eat & Drink

Travel

Travel

Style

Style

Beauty

Beauty

Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness

Home & Decor

Home & Decor

Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Weddings

Weddings