Whether the headlines cite Ozempic or obesity, Western media remains fixated on weight. But in East Asia, the conversation takes a different shape — one that equally reveals cultural expectations, though fewer dare to question it.

As weight-loss drugs like Ozempic surge in popularity, so does society’s unsolicited commentary on women’s bodies. In the West, speculation runs rampant: Did that celebrity lose weight “naturally,” or are they secretly on medication? While the discourse is often framed as a demand for transparency or a critique of unrealistic beauty standards, it has also revived a familiar cultural obsession — thinness as the ultimate measure of a woman’s worth.

What happens when we shift the lens to East Asia? A Hong Kong native and member of Team Sassy has experienced this tension firsthand. After losing weight with Saxenda, an Ozempic alternative, she found herself caught between two conflicting narratives: Western body positivity rhetoric and East Asian beauty standards. Here, thinness is so normalised that no one questions how it’s achieved — but online, she found herself mulling over the insinuation that she should have “loved herself” enough to remain her former size.

The reality, of course, is that women are shamed no matter what: for being overweight, for being underweight, for losing weight “the wrong way.” So why do these double standards persist? And what do they say about the pressures women face in both societies?

Read More: Hack Your Algorithm — Curating A Positive Social Media Presence

Editorial Note: This article explores broad societal trends, but individual experiences, preferences and bodies vary. No culture is monolithic.

The Unspoken Rule Of Thinness

This Team Sassy member recalls being called “肥妹” (chubby girl) by friends, family and even strangers since childhood, which chipped away at her confidence over time. As an adult, she set a goal to lose 10kg — landing her at a weight that would be considered gaunt in the West, but “normal” in Hong Kong.

Her decision to try Saxenda was partly pragmatic (she led an active lifestyle but had never achieved significant weight loss through diet and exercise alone) and partly influenced by the same Hollywood “before and after” narratives that dominate Western media. But in Hong Kong, no one batted an eye at her methods.

“I knew losing that much would make people in the US or UK think I was insane,” she admits. “But here, it was applauded.”

To understand her experience, it’s helpful to look at the example set by regional media, through which It Girls like Jennie Kim of BLACKPINK establish the de facto blueprint of contemporary East Asian beauty. The K-pop idol and Chanel ambassador is celebrated not just for her talent, but also for her “elegance” — a trait euphemistically intertwined with her “petit” and “delicate” frame.

To put things in perspective, Jennie reportedly weighs between 45kg and 50kg — at least eight kilos less than the average South Korean woman. No one has accused her of unhealthy dieting (despite the known “height minus 120” industry standard, where female stars’ weight is expected to align with that calculation), let alone of taking Ozempic. Instead, her thinness is praised, even earning her the title of “Pilates princess.” This blind acceptance sends a clear message to young women: Thinness isn’t just desirable; it’s expected.

Read More: Life Without Kids: Honest Conversations With Child-Free Women

Battling Between Conformity & Scrutiny

Our team member’s experience with Saxenda underscores the dissonance between East Asian norms and Western health rhetoric. She lost five kilos in two weeks (likely water weight initially), tracking changes in body composition with clinical detachment. Side effects — dizziness, a fainting episode — were shrugged off by peers more intrigued by her results than concerned about risks.

“People asked me if Saxenda ‘targeted belly fat,’ like I was a walking infomercial,” she says.

The lack of critical thinking alarmed her: prescriptions were reduced to gossip fodder, their medical gravity ignored. Meanwhile, her weight loss became public property; a spectacle to be praised, not a personal health decision to be respected.

Herein lies the paradox: East Asian beauty standards demand thinness but absolve women of prioritising health, while Western discourse pathologises weight loss unless it’s “earned” through virtuous struggle. Both frameworks reduce women’s bodies to sites of communal commentary — one through blind reverence, the other through incessant scrutiny.

Read More: Why Carb-Free Diets Don’t Always Work For Women

How Did We Get Here?

We know that beauty standards are shaped as much by contemporaneous cultural and societal expectations as by aesthetics. From Song Dynasty-era paintings of slender, willow-like women to modern media tropes, East Asian femininity has long been associated with fragility and, inextricably, with thinness.

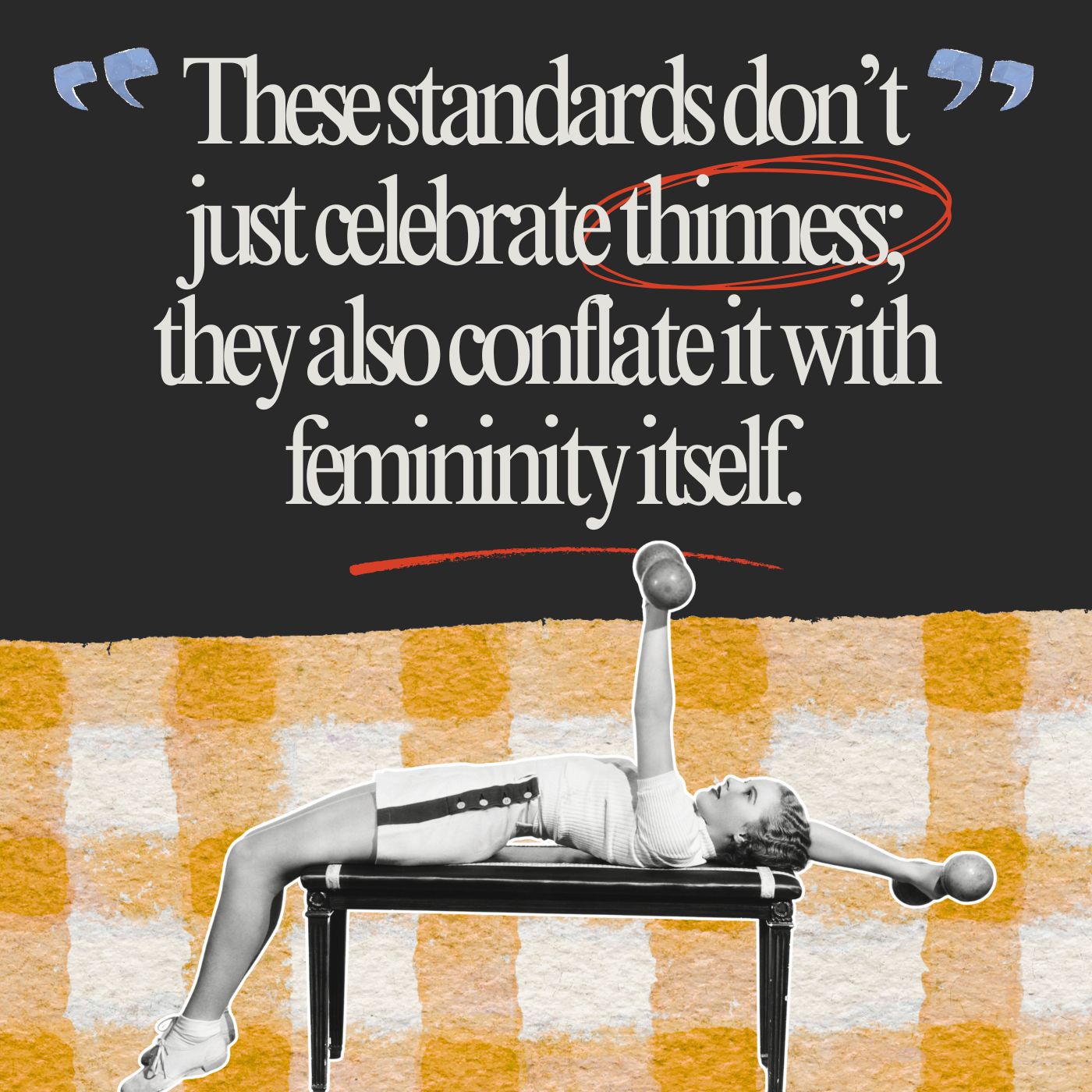

This ideal extends beyond weight, manifesting in other beauty trends that reinforce the link between delicacy and femininity. Take, for example, the regional preference for Jennie’s 幼態感 (“baby face”) aesthetic — a concept that, whether consciously or not, perpetuates the infantilisation of female sex symbols. Similarly, viral trends like 仙女落泪 (“the fairy wept, and the man knelt”) romanticise the image of beautiful women crying, framing vulnerability as an aesthetic ideal. Even the popular 可甜可盐 (“salty and sweet”) trope, which Qingyue Sun critiques in an essay on Chinese femininity, reduces female expression to consumable flavours, demanding women to “seamlessly switch between domineering and soft, sexy and cute.”

Together, these standards don’t just celebrate thinness; they also conflate it with femininity itself, equating a woman’s worth with beauty, and her beauty with fragility.

Read More: A Non-Binary Hong Konger Talks Top Surgery & Trans Joy

Two Sides Of The Same Coin

In the West, thinness is equally prized, but for different reasons. Individualistic cultures like the US and UK frame weight loss as a testament to one’s discipline and self-control — traits historically tied to virtue. This is why Ozempic users, especially women, face backlash: it is seen as “cheating or evidence of a lack of willpower,” as Boston-based obesity medicine physician Chika Anekwe puts it, because the drug bypasses the work that makes thinness morally laudable.

East Asia, by contrast, mirrors Western diet culture of the early 2000s — thinness is openly glorified, with little pretence of body positivity. The lack of scrutiny might feel like a reprieve from Western judgment, but it also leaves no room to challenge the standard itself.

Our team member sums it up best: “In Hong Kong, no one asks how you lost the weight. They just congratulate you.”

And this praise, she says, did not feel like freedom from scrutiny; if anything, it made her and those around her even more aware of her weight. When confronted with Western rhetoric, this reality was all the more unsettling.

The Path Forward & Redefining Beauty

For women in Hong Kong, then, the pressure isn’t just about looking a certain way; they must also navigate two worlds that claim to value women’s choices while offering none at all. Until we dissociate weight as a signifier — of femininity, discipline or anything else — women will keep losing, no matter what the scale says.

A promising way to lessen the power of the scale is to start open, supportive cultural conversations, especially among women. By connecting authentically, sharing experiences and uplifting each other, we can foster a more compassionate perspective and illuminate a path towards the acceptance and body neutrality we all crave.

Read More: What It’s Really Like Being In An Open Relationship

All images courtesy of Sassy Media Group. The experienced described in the story is not the author’s.

Article inspired by Qingyue Sun‘s 2023 essay “New femininities and self-making in contemporary Chinese beauty influencing.”

Eat & Drink

Eat & Drink

Travel

Travel

Style

Style

Beauty

Beauty

Health & Wellness

Health & Wellness

Home & Decor

Home & Decor

Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Weddings

Weddings